Preface: In December, High Country News published a story of mine titled, Is nuclear energy the key to saving the planet? It got a very strong reaction. Some readers seemed to breathe a sigh of relief: Now that HCN has waded into these waters, they could, too. Others, particularly from the No Nukes camp, were livid. Several called it an ad for the nuclear industry. Meanwhile, it kind of went nuts on reddit. I hadn’t intended for the story to take a position on the matter. I just wanted to profile this movement, which I found interesting. The following essay is sort of a more impressionistic take on the whole thing, and includes some scenes and characters that got cut from the HCN story in order to get it to fit in the allotted space.

Under a blanket of smoke from wildfires burning all over the West, the sun reduced to a blurry orange blob, I drove west from Idaho Falls, sailing past rolling plains of wheat, where huge thrashers looking more than two lanes wide kicked up big clouds of dust that vanished into the smoky haze. Raptors perched on nearly every fencepost or power pole I saw, scanning the lava flows and sage plains for lunch. And then the signal that I’m amidst the vast landscape coopted by the Idaho National Laboratories: bright yellow signs warning humans — and grazing cattle — to stay on that side of an invisible line. I shuddered to think of the plight of illiterate cows.

I was out there in search of the future of nuclear power, which is increasingly being seen as a necessary component in the fight to stem a global warming catastrophe, by looking at its past, specifically Experimental Breeder Reactor I, where for the first time a nuclear fission chain reaction was used to generate and transmit electricity in 1951.

EBR-I appears today much as it did in 1963 when the team of workers clocked out for the last time and headed down to the bar at “Atomic City” before making the commute back to their homes in Idaho Falls or Pocatello. It’s got an industrial retro-futuristic feel, with its control panels and knobs and valves and other apparatus that possess the characteristic sleek chunkiness of mid-century high-tech design. A temperature gauge for the “rod farm” goes up to 500 degrees centigrade, and if you look closely you’ll see a red button labeled “SCRAM” that, if pushed, would have plunged the control rods into the reactor, thereby “poisoning” the reaction and shutting down the reactor. Outside sit two huge experimental jet-engine reactors, symbols of the promise nuclear energy once held.

Those were heady times. By whacking a uranium atom with a neutron and splitting it, the technicians on that cold December day launched a chain reaction that released heat that generated steam that turned a turbine that generated electricity that illuminated a string of lightbulbs and then powered the entire facility. Because it was a breeder reactor, the reaction actually created more fuel for future reactions — almost a perpetual motion machine. Scale that up and, for pennies per megawatt-hour, it could power our increasingly electrified society, all without burning any coal or oil or damming any rivers.

After decades of faltering and of suffering from a terrible negative perception, nuclear energy’s golden days may be making a comeback. Climate hawks, scientists, energy wonks, eco-modernists, and a handful of politicians are pushing hard to bring nuclear back from the brink, and to use it to save the world from climate change. The movement spans a broad spectrum, from extremists like Michael Shellenberger, who scolds even those who dare say that nuclear could work well with renewables, to more reasonable folks, like Emma Redfoot, whom I profiled for High Country News in December of last year.

Shellenberger has become a full-throated advocate of building new nuclear reactors as quickly as possible. Others take a more tempered approach, acknowledging that nuclear power has big drawbacks but that continuing to recklessly burn fossil fuels for power is far more dangerous than including nuclear in the global energy toolbox.

I was skeptical going into this story. And when I went to EBR-I, I was both fascinated and sort of creeped out. After all, I came of age in the 1980s, in the aftermath of the Three Mile Island accident, when the No Nukes movement was going full steam, and when the threat of nuclear annihilation lingered on the horizon. When I was in sixth grade, I did a science fair project in which I modeled what would happen to various cities if — when — they were hit by a nuclear missile; a few years later my buddies and I created a Dungeons & Dragons style role playing game that took place in a post-nuclear holocaust American Southwest. Mushroom clouds and nuclear winter saturated pop culture — 99 Luft Balloons, The Day After, War Games. The Chernobyl disaster unfolded when I was sixteen. And I grew up in the shadow of a uranium tailings pile.

Baby Boomers and Gen Xers think of nuclear energy and nuclear bombs as being inextricably intertwined. That’s probably because fission was used to blow people up before it was used to light up lives. Besides, a reactor is basically a bomb-fuel producer: Neutrons bouncing around during the reaction are absorbed by uranium-238, becoming plutonium-239, which can be used as is in “dirty bombs” or further enriched to become the fissile material in a nuclear weapon. As deadly as coal may be, its waste can’t be turned into a human-evaporating monstrosity. So it was that touring EBR-I, and seeing the various odes to atomic fission scattered throughout, made me uneasy, in the same way that touring the Manhattan Project museum in Los Alamos gives me the heebie-jeebies.

On the way back to Idaho Falls I saw a shimmer through the haze, something that resembled the polished dome on a mosque, or a structure on a colony on Mars from a Ray Bradbury story. It was the containment building for EBR-II, which was shut down and razed in the 1990s, following the Chernobyl disaster, when public opinion of nuclear power was at a low point. A room in EBR-I is dedicated to its younger, late sibling. Such is not the case for reactor SL-I, which once sat a few miles away from EBR-II. In 1961 one of three workers there, perhaps intentionally, had pulled the control rod too far out of the reactor, causing the chain reaction to go haywire. The reactor facility exploded, the water pressure so strong it impaled a man onto the ceiling of the containment structure. The other two died, as well, making it the first fatal nuclear reactor accident ever. Rumor has it the men are buried in lead caskets.

***

As I was researching this story and reading and listening to all of the arguments in favor of upping the amount of nuclear power in the nation’s energy mix, I was taken back to the 2008 Democratic National Convention, when I sat in a Denver bookstore and listened to Carl Pope, then-president of the Sierra Club, rhapsodize about the virtues of natural gas as a “bridge” fuel that could wean us off of dirty coal and even petroleum and lead us into a clean energy future.

Shellenberger would certainly bristle at the comparison — he asserts that the natural gas and renewable energy industries are waging a “war on nuclear” — but I can’t help but see the similarities between pro-nuclear rhetoric and Pope’s circa 2008 natural-gas-as-bridge speech. After all, they both want to displace coal with a relatively clean energy source. Both of them have the big picture in mind, namely the looming climate catastrophe that will come sooner rather than later if coal isn’t abandoned quickly.

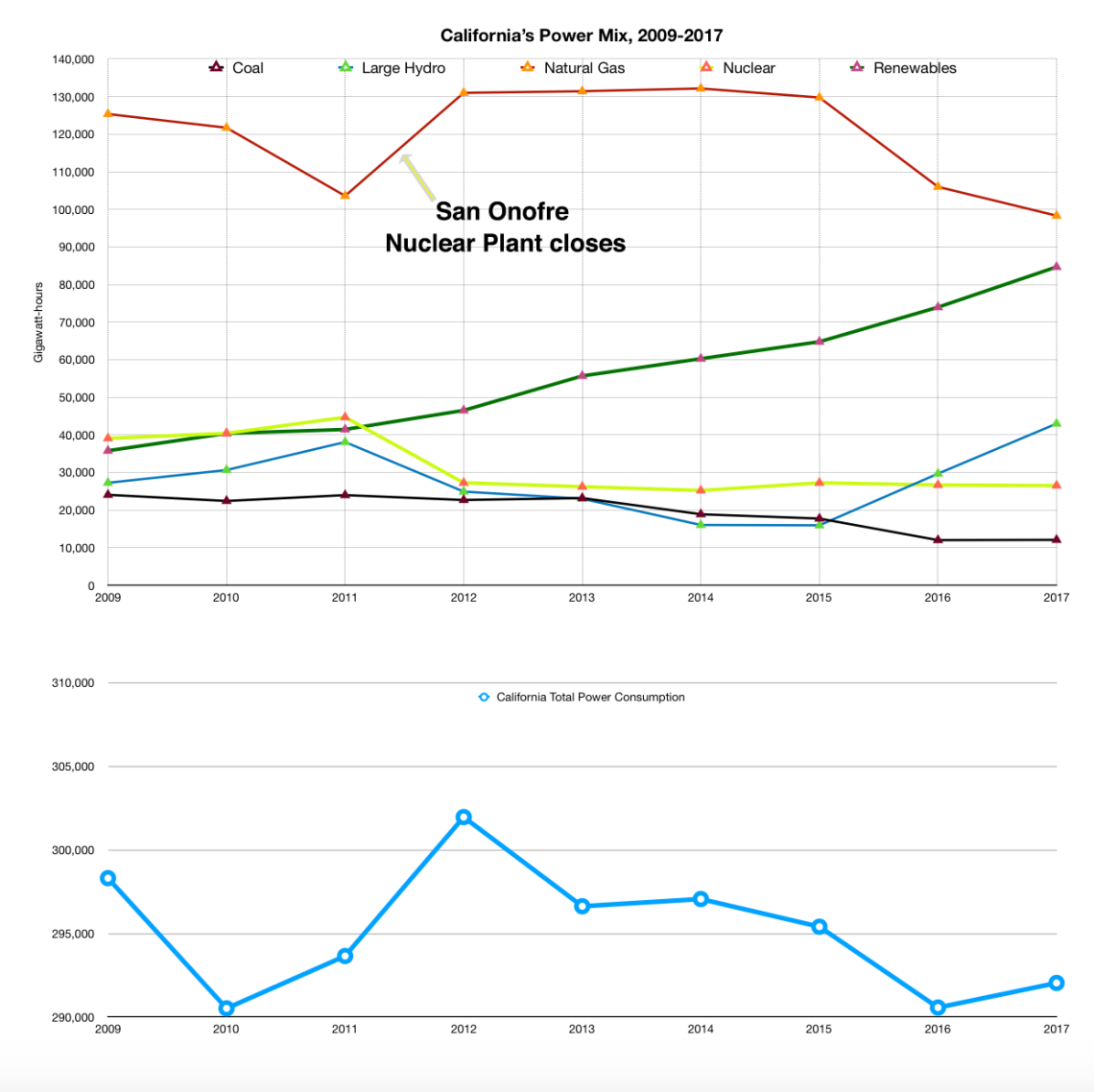

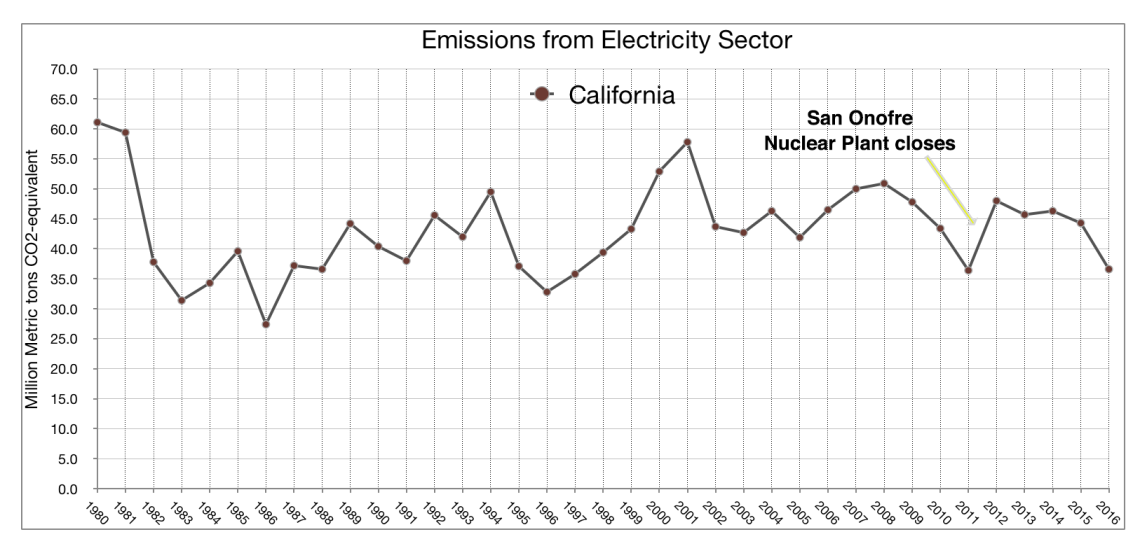

The flood of natural gas has certainly helped. Back in 2008, utilities burned more than 1 billion tons of coal per year to generate about half of the nation’s electricity, while natural gas generated just 21 percent. In just one decade, the tonnage of coal burned was slashed in half, decreasing annual carbon emissions from the electricity sector by some 700 million tons. There hasn’t been a parallel buildup of nuclear power capacity, but when San Onofre Nuclear Generating Station went offline in early 2012, emissions for California’s electricity sector shot up considerably.

Yet at the same time, the natural gas boom has ravaged the landscape, pipelines have burst, sometimes with fatal results, methane leaks in unknown quantities, offsetting the gains achieved from the displacement of coal. And so there is another similarity between Pope’s path and Shellenberger’s: both of them seem to be missing the trees for the forest. They are so focused on reducing greenhouse gas emissions that they don’t even notice the on-the-ground impacts of their chosen technologies.

Yet at the same time, the natural gas boom has ravaged the landscape, pipelines have burst, sometimes with fatal results, methane leaks in unknown quantities, offsetting the gains achieved from the displacement of coal. And so there is another similarity between Pope’s path and Shellenberger’s: both of them seem to be missing the trees for the forest. They are so focused on reducing greenhouse gas emissions that they don’t even notice the on-the-ground impacts of their chosen technologies.

For a long time, nuclear waste — those in the industry prefer the term spent fuel — was nuclear’s dirty secret. Now, the nuclear evangelists like to talk about it. They point out that the 80,000 metric tons or so of spent fuel that U.S. reactors have produced since 1968 could all fit onto a single football field, stacked just 24 feet high. That all of that material is accounted for, and its storage in dry casks is highly regulated and monitored. Contrast that to coal power plants, which annually kick out tens of millions of tons of nasty flyash, slag and other solid waste, in addition to all the toxins and particulates that spew from the smokestacks. Or the billions of gallons of briney, contaminated “produced water” that oil and gas wells vomit each year. Both of these enormous waste streams are toxic, can be radioactive, and federal regulations on their disposal are virtually nonexistent.

These stats are accurate, the comparisons apt. But they reveal a blind spot for nuclear evangelists: The millions of tons of additional waste produced, and the human toll taken, by uranium mining and milling. Sarah Fields has been butting heads with the nuclear industry since before the pro-nuke millennials were even itches in their daddies’ britches, and has spent decades exposing the dark side of this so-called clean energy source.

I chatted with Fields on the patio of a cafe in Monticello, Utah, near where she lives and has her office, in late August. The wind had blown the smoke away, and the air was clearer than it had been for much of the summer, but the short-lived monsoon had vanished, leaving behind cloudless skies and blistering heat at the end of one of the driest years for the Four Corners Country on record. Fields is the founder and sole employee of Uranium Watch, and has been a thorn in the side of Utah’s uranium industry for nearly 40 years.

In 1987, Fields and her husband and kids moved from San Luis Obispo — just a couple miles inland from Diablo Canyon — to Moab, Utah. There, the Atlas uranium mill, located on the edge of town along the banks of the Colorado River, was about to shut down for good, thanks to the crash of the domestic uranium market. The owners and the federal government had to figure out what to do with the 16 million tons of radioactive tailings that sat onsite and that was leaching into the water supply of millions downstream. Fields jumped into the fray, watchdogging the process for the Sierra Club and Friends of Glen Canyon before starting her own one-woman show, Uranium Watch, in 2006.

The Atlas pile was just one shard of the toxic legacy left behind by the U.S. uranium industry, which ravaged landscapes and lives in the American West from the 1940s to the 1980s. The International Agency on Atomic Energy estimated that the U.S. uranium mills had produced 190 million metric tons of uranium tailings for energy production, alone, containing radioactive daughters of uranium such as thorium and radium, along with heavy metals such as copper, arsenic, molybdenum and vanadium. You’d have to stack that about 15 miles high to fit it on a football field.

While Shellenberger’s pro-nuclear rants compare the relatively small death tolls at Fukushima and Chernobyl to those resulting from natural gas pipeline explosions and coal-fired air pollution, they rarely touch on the actual production of nuclear fuel, or uranium mining and milling. Rarely does the debate mention the countless Western uranium miners and millworkers — both Navajo and white — who got cancer, or came down with kidney disease or other maladies due to exposure to uranium and its radioactive “daughters.” We hear even less about the people who lived near the mills or mines, and ended up drinking contaminated water or breathing the dust that alit over the giant tailings piles.

Fields would like to change that. With a shy smile, big blue-gray eyes, and straight silver hair, she is tireless in her activism, most of which is funded by her. She puts countless miles on her decades-old Toyota station wagon driving to hearings and conferences and site visits. She has learned the art of activism on the fly, brought herself up to speed on the myriad technical issues of her focus issue. And she’s an expert at badgering agencies with Freedom of Information Act requests to get them to cough up pertinent documents such as letters concerning a 26,000-ton pile of uranium tailings that was inundated by Lake Powell in the 1960s.

Over the years Fields has continued to monitor the Atlas Mill cleanup — which won’t be completed until approximately 2030 — and fought hard to stop a proposed nuclear plant in Green River, Utah. She’s kept an eye on the White Mesa uranium mill outside of Blanding, Utah; the Daneros uranium mine that lies just outside the boundaries of the Obama-drawn boundaries of Bears Ears National Monument.

She is alert to moves to re-open or expand other mines in the region, but she doesn’t expect any sort of flurry of uranium mining anytime soon, even if new nuke plants get built. That’s because globalism has reduced mining and milling in the United States to a mere shadow of its Cold War self. In 2017, U.S. uranium producers kicked out a record low of just 1,150 tons of uranium concentrate, or about five percent of the fuel consumed by domestic nuclear plants (compare that to the 600 million tons of coal burned in U.S. plants last year). The other 95 percent is imported, mainly from Canada, Australia, Russia and Kazakhstan. These countries can supply uranium for far cheaper, in part thanks to government subsidies like those that propped up the U.S. uranium industry from the 1950s to the 1980s. Plus, because of uranium’s high energy density, it is relatively cheap to ship overseas.

Fields is looking at the issue through a local or regional environmental justice lens. Redfoot and Shellenberger are seeing it through a global, climate change lens. The key is to reconcile the two.

***

One of the thing that strikes me about the conversations around tackling climate change, regardless of whether it’s with nuclear power, natural gas, or wind and solar, is that it almost always goes in the direction of building more: More wind turbines, solar farms, nuclear plants, more coal plants with carbon capture, more green buildings. “The anti-growth anti-people extremists who started the anti-nuclear movement were wrong,” Shellenberger once wrote. “More energy is good for people, and it’s good for nature.”

It’s the mantra of capitalism: Survival and infinite growth are one and the same.

What about just using less of everything?

I thought about this as I drove from Idaho Falls eastward along the Snake River, passing by flapping wind turbines sprouting from hilly grasslands and then the Palisades hydroelectric dam, and as I continued into Wyoming before turning south out into pronghorn country. And I especially thought of this idea as I made my way through the streets of Jeffrey City, Wyoming.

It’s not much of a city, more like a dried out husk. There are streets here and sidewalks and gutters. Here’s a Jackalope Drive and a Uranium Drive and, inexplicably, a Scarface Drive, and even a cul de sac or two. But the trailers that once lined the streets are mostly gone, a handful of old apartment buildings sit empty, and flowers and weeds are slowly reclaiming the asphalt streets. Jeffrey City née “Home on the Range” came to be in the 1950s, when uranium prospectors converged on the area and opened mines and mills, then the population exploded in the 1970s to about 5,000 people as big mining interests moved in. But by the early 1980s, after the feds stopped propping up the industry and imports started flooding in, Jeffrey City busted, hard, leaving little more than the brand new school facility that never really got used.

Scattered about around the town are remnants of partially remediated uranium operations long abandoned. And to the south, down a dusty gravel road that goes through Crooks Gap, a few operations still hang on. I followed the road just to see what I could see, which turns out to be not much more than signs telling me to keep the hell out — along with the biggest golden eagle I’ve ever seen, my passage interrupting its meal of some stinky carrion. I passed the Sheep Mountain Mine. Energy Fuels, the owner, calls it “one of the largest uranium projects in the U.S.,” though it’s not producing anything. And then Ur-Energy’s Lost Creek in situ operation, which is operational and has had at least 40 violations, spills or “reportable events” since 2013, including a release of 1,625 gallons of uranium-containing production fluid just days before I passed by.

As I topped a subtle rise in the seemingly featureless landscape something changed — through the smoky haze I could see skeletal towers jutting up from the land. I had passed from uranium country into natural gas country. I had to pull my little rental car over to let the big, barreling trucks pass by. This boom, too, had ebbed years ago, but drilling continued nonetheless, as did production, that gas being piped off to distant households and power plants.

When Shellenberger said that more energy was good, he was echoing former Sierra Club director Will Siri, who, in 1966, wrote: “Nuclear power is one of the chief long-term hopes for conservation… Cheap energy in unlimited quantities is one of the chief factors in allowing a large rapidly growing population to preserve wildlands, open space, and lands of high scenic value … With energy we can afford the luxury of setting aside lands from productive uses.”

I sailed through ecosystems fractured by thousands upon thousands of oil and gas wells, past the towering smokestacks of coal power plants and the gaping mines that feed them, through the haze of a burning planet, and past the still-contaminated ruins of uranium country. The mantra kept on echoing inside of my head: “More energy is good for people. Good for nature.” And somehow, I just couldn’t believe it.

###

Jonathan P. Thompson is a contributing editor at High Country News and the author of River of Lost Souls: The Science, Politics, and Greed Behind the Gold King Mine Disaster. Get a copy of River of Lost Souls.

Jonathan P. Thompson is a contributing editor at High Country News and the author of River of Lost Souls: The Science, Politics, and Greed Behind the Gold King Mine Disaster. Get a copy of River of Lost Souls.

“(Thompson) combines science, law, metallurgy, water pollution, bar fights and the occasional murder into one of the best books written about the Southwest in years.”

— Andrew Gulliford, historian and writer, in The Gulch magazine.

Recently a blowout occurred in Brazil of a mill catch basin killing reportedly 200 people. Wonder whether consideration is ever given to risks like this being created by overzealous environmental management?

LikeLike